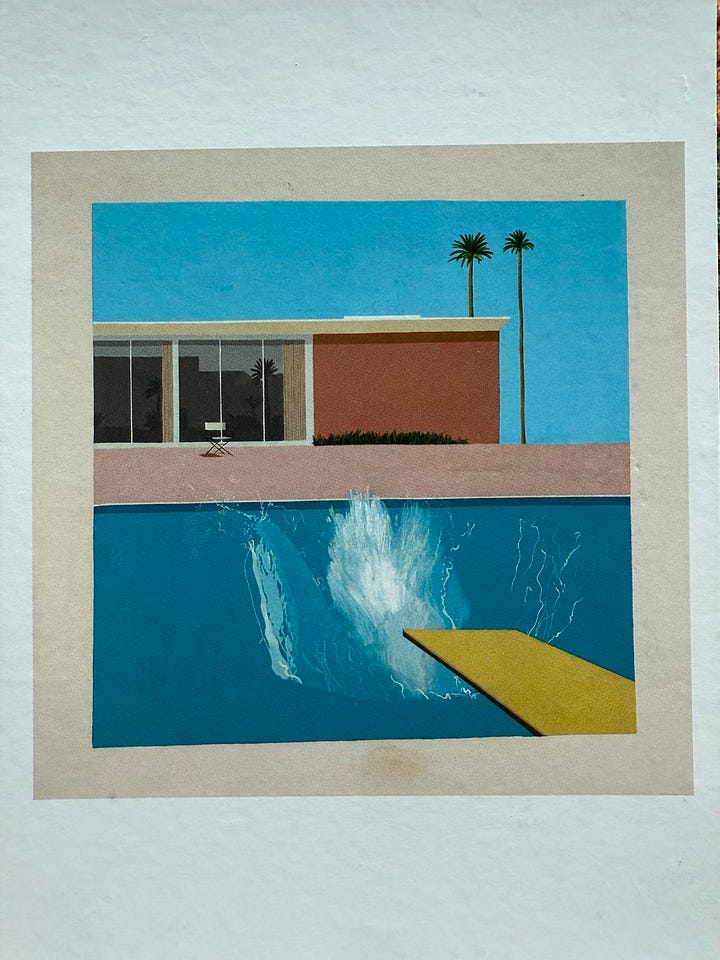

Splash

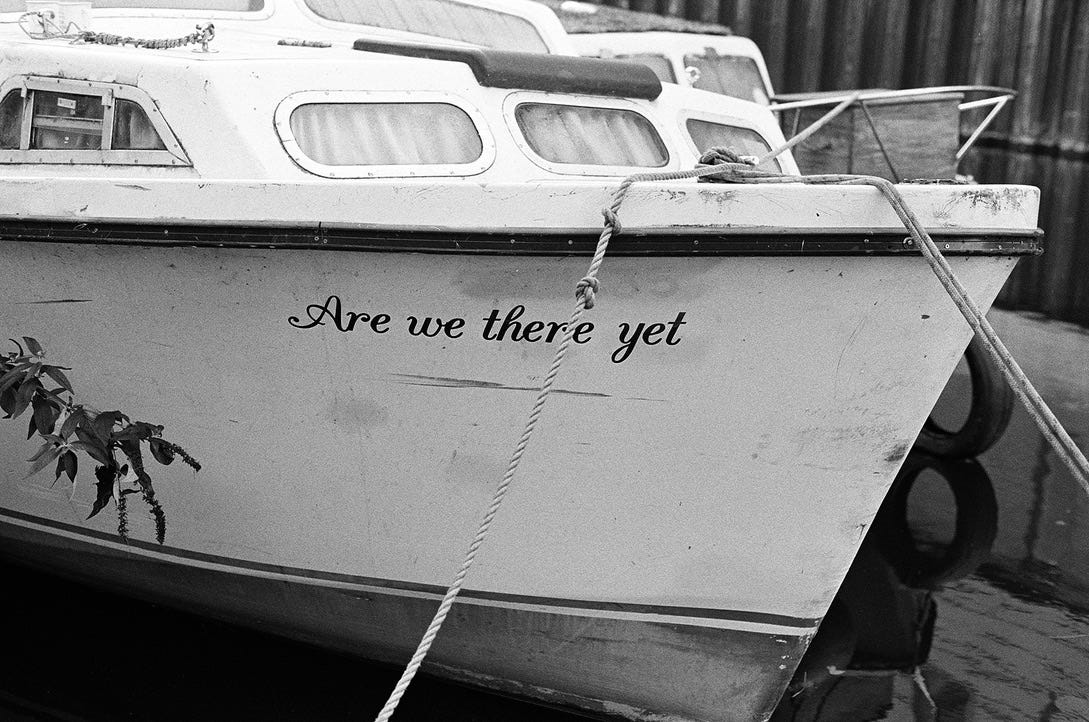

How will you go about finding that thing, the nature of which is completely unknown to you?

It’s an unsettling feeling to be in between things. My friend David calls it the abyss. A year and a half ago, I left the job I’d had for seven years, and for much of 2024, I was in it. The abyss. It’s not as dramatic as it sounds (it’s actually a beautifully transformative place), but it can be scary. Now that I’ve landed on the other side, I keep finding myself in conversations with friends who’ve just taken a leap of faith. I decided to write down a few reflections that tend to come up. If you’re in the midst of a big life change, I hope they resonate. If you’re not, fair warning: some of this might sound a little strange! I’m diving straight in, but skip to the end if you’re looking for quick, tactical bullet points.

I occasionally make introductions for people in explore mode. If you're open to connecting, feel free to email me at lola@asylum.vc with a few words about yourself. Always double opt-in.

Being nobody

When you first jump, every minute feels momentous – there’s a lot shifting internally and externally. What struck me most in those early days was the feeling of being nobody. I used to represent a brand, have something to offer (including capital). There was a built-in sense of usefulness and belonging. Overnight, that was gone. When people asked what I did, I’d say, “I’m Lola, and right now I’m just a person.” It started as a joke, but it ended up feeling accurate.

There’s something both disorienting and liberating about being stripped of identity. Like a shellfish without a shell — exposed, unprotected. Your ego gets humbled fast. You realize you’re not indispensable, that the world continues just fine without you. If you let it, that realization becomes clarifying. Without something to prove or protect, you can start asking different questions. What matters when no one’s watching? What risks do I take when I have nothing to lose?

I wasn’t just letting go of a job, I was letting go of how I saw myself and how I imagined others saw me. I disappeared for a while. I walked, I slowed down, I lived more internally. Then when I was ready to explore more actively and come back into the world, I was very intentional about maintaining a level of silence and stillness.

“In a world that entices us to browse through the lives of others to help us better determine how we feel about ourselves, and to, in turn, feel the need to be constantly visible, for visibility these days seems to somehow equate to success, do not be afraid to disappear, from it, from us, for a while, and see what comes to you in the silence.”

— Michaela Coel

The abyss

Being in the abyss feels like a quest for truth. For the first time in my life, I wasn’t operating under the umbrella of an institution – no school, no university, no company. Just me. It was a rare opportunity to be fully honest with myself. I began to treat it like a game built around two commitments: first, to confront my fears head-on; second, to prioritize sensing over thinking.

Fear

A lesson I keep learning is that we’re often our own worst enemies. Fear is meant to protect us, but it often becomes a cage. I’ve come to believe that decisions made from fear are rarely the right ones. So I made it my responsibility to notice when fear showed up, and to intentionally move in the opposite direction. Practically, that meant tracking what scared me — rejection, irrelevance, not knowing, being vulnerable — and choosing to move toward those things instead of away. Not just professionally, but in every part of my life. Consistently running toward fear builds a kind of confidence few other experiences can offer. And in times of uncertainty, that kind of courage becomes even more essential.

Sometimes it was small acts, like sending a professional love letter when I felt a spark. Other times it was bigger. Just weeks after I quit, the October 7 attacks in Israel happened. I was overwhelmed by the horror of the violence, the war that followed, and the impossibility of the discourse around it. I was also afraid: of saying the wrong thing, of losing friends, of what might come next. But instead of retreating, I shocked my system again. I teamed up with my friend Ramzi to host a series of listening circles: we invited people from all backgrounds to sit with discomfort, to “open the wound,” and speak honestly about what was and is happening. The circles are still running monthly, and the community has grown to 70 people.

Sensing

The second commitment — listening to my body more than my brain — took longer to understand. A few months in, I was venting to an entrepreneur I admire. “I’m just tired of thinking about what’s next,” I said. “I’m bored of talking about myself. Bored of the whole thing.” He replied: “That’s great. You had to get to the end of thinking to realize that thinking was never the answer.” I didn’t fully get it then, but I do now. I’ve always lived in my head (I’m an electrical engineer!), I believe in logic and systems. I like to sense make and I over-intellectualize most things. But the truth is, the most important decisions in my life haven’t come from thinking. They’ve come from somewhere deeper, a kind of embodied knowing. Less like a decision, more like a recognition. As if something in me already knew, and my only job was to get out of the way.

You probably know the feeling: when you meet someone and just know they’re your person. When you walk into a room and something in you says, this is it. No pro-con list. No overthinking. Just a full-body yes. That’s how I felt when I first met Hummingbird, back when I was still a student. And it’s what I was quietly chasing, and eventually found again, with Asylum. Practically, this meant exposing myself to a lot: conversations, experiments, part-time projects, even new industries. But instead of analyzing every interaction, I started paying attention to my body:

Was I energized after?

Did it linger in my mind?

Did I have opinions and ideas on the project as if it could be my own?

It became a quiet practice of self-attunement and noticing. Some opportunities looked perfect on paper but left me cold, others made less sense — like moving to America for Asylum, after nearly a decade of living happily in London — but lit something unmistakable in me. I’m usually resistant to sharing exactly how that feeling manifested, because it will look different for everyone, but here’s a snapshot: I couldn’t stop thinking about it. People told me my tone and body language shifted when I spoke about it. I felt like I was a part of the firm before even discussing that potentiality. Like there was an invisible rope was pulling me and I had to follow it.

Illusions

After I left my job without a plan, one of the questions I got was: “Isn’t that bad for your career? What if there’s a gap on your resume?”. My first thought was: if someone genuinely cares about that, they’re probably not someone I want to work with. My second thought was: what even is a career? Can you point to it? Can you show it to me? It’s not a real thing, it’s a concept, a model we use to make sense of our lives and choices. This was part of a bigger realization I kept coming back to around “illusions”: how often we confuse the models we’ve built to understand the world with reality itself. A career is not a tangible object, it’s a framework. Helpful at times. But frameworks are meant to serve us, not the other way around. One of the hardest and most freeing parts of being in transition is realizing that the structures we use to define ourselves don’t always apply. That doesn’t mean they are wrong or useless, but more that they are scaffolding, not foundations. I’m not saying we should live without structure, or toss out every tool that helps us navigate. But I do think we need a healthy skepticism: are the models we’re using still serving us, or have we started quietly serving them instead?

Timeline

Being a bit practical for a second here. Leaving the only job I’d ever had – something I genuinely loved, and a big part of my identity - was the right thing to do but still felt like a shock to the system. Quite early on in my journey, I read the book “Transitions” by William Bridges, which became a useful lens to understand what I was going through. According to Bridges, a transition unfolds in three stages: an ending, a neutral zone, and a new beginning. We often skip the neutral zone and rush to what’s next. But it’s in the in-between, when roles, routines, and identity anchors fall away, that the richest transformation can happen. What I thought would be a couple of months turned into a full year — not because I was drifting, but because I realized how fertile the neutral zone could be if I let it happen on its own terms. I didn’t set a deadline for starting something new, I trusted the next step would make itself clear. Here’s roughly how the year unfolded.

Ending I jumped and then rested. I had very minimal contact with the industry. I went on a weeklong retreat, followed by a weeklong photography course in Italy with a war photographer. The stillness was strange but essential. I spent January and February in a slower rhythm: reading, taking long walks, doing mid-morning yoga, and spending unstructured time with friends and family. Where I’m usually squeezing visits to my hometown into a rushed two-day sprint, I could simply be there and be present with my loved ones, for both the big and small moments.

Neutral zone From March to October, I entered a more proactive exploration phase. I worked part-time at another venture fund (hi Kindred!), joined a transition program called Downshift, and experimented with different projects, both in and outside of tech. It was busy — my partner at the time used to joke that I was working more than full-time — but I still left space for things to emerge. Some of the most meaningful experiences didn’t belong on any roadmap: I deepened my learning of Turkish through many lessons, worked closely with other friends who were investors and builders, photographed my friends’ weddings, among other things.

New beginning Between October and December, I made my final decisions, took a two-week vacation, prepared my O1 visa application, and got ready for the next chapter.

Commitment

I don’t romanticize floating. I’m not someone who believes in constantly jumping from one thing to the next, or permanently reassessing everything. Most things – jobs, relationships, places – become great because you stick around and decide to invest, even when it’s uncomfortable or uncertain. I was at Hummingbird for 7 years, I built a life in London for nearly a decade before moving to New York, and I have had my closest friends by my side since before we could speak. I say all this because sometimes transitions get framed as a kind of freedom from commitment. For me, it was the opposite: the point wasn’t to escape, it was to figure out what was worth committing to next. It can sometimes be a source of pressure. The next thing must be the Right Thing! Forever! Paradoxically, what helped most was holding both truths at once — the desire to commit deeply and the understanding that loosening the grip would lead to a better outcome.

Congratulations

This is truly the one thing I say most when someone finds themselves in the abyss: congratulations. I am so excited for you. You’re stepping into a chapter that will teach you more than you expect. Because ultimately, we are always in some kind of life transition, shedding an old skin, sitting raw and exposed until a new one forms. Trying to do it with honesty. It won’t feel joyful every day, but it will feel true. There’s no hiding when you’re on your own. And that, really, is the gift :)

Quick tactical stuff

Messiness is a feature, not a bug. If things don’t feel a little chaotic or uncomfortable, you’re probably not letting the transition do its full work.

Document everything. Write things down. Take pictures of what speaks to you. You’ll think you’ll remember but you won’t, and the early signals are worth revisiting later. This is something I regret not doing more.

Finding a community of people who are also in transition is very helpful. The rest of the world won’t necessarily understand and it’s comforting to speak the same language. One trick I used: I asked everyone I met if they knew someone else in a similar phase.

If you have a partner, loop them in. They’ll play a meaningful role in your process. It might be unsettling for them too and communication is important.

If you’re an achiever (hello enneagram 3! Test here if you don’t know what you are), practice sitting in the discomfort of not producing. You won’t lose your ambition or your edge, they’re still there, just waiting to be channeled differently.

There is no silver bullet. No one has the answer. All tools eventually point inward.

The transition is a very active process. Even if your process is intuitive, it doesn’t happen on its own or outside of you. You have to fully show up.

Very annoying, very cliché… but the path does reveal itself :)

Resources

If you’re looking for inspiration or support, here are some resources that helped me along the way:

Communities and experiences

Steve Schlafman’s transition work

Next Play newsletter & events

VAWAA is the platform I used to find my photojournalism course in Italy

Boyd Varty’s work

Writing

Transitions by William Bridges

The Creative Act by Rick Rubin

Letters to a Young Poet by Rilke

Unfolding by Henrik Karlsson

You and Your Research by Richard Hamming

Commencement speech by John Gardner

This is so good. Wow. Thank you for writing this. It’s so human. So pure. So insightful… and so much more! Thank you!

It’s the 3rd time I’m reading this, wanting to restack a new bit every time. Feels very real and resonating. Pls write more of this :)